-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Grants

-

IDF surveys

-

Participating in clinical trials

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Clinician education

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Grants

The newest classification of primary immunodeficiencies (PIs) lists 45 different PIs that are considered predominantly antibody deficiencies—that is, disorders that mainly affect a person’s ability to produce working versions of one or more types of antibodies. Although all PIs are rare disorders, antibody deficiencies are the most common type of PI.

Why antibodies are so important

Antibodies, also known as immunoglobulins (Ig), are a critical part of the adaptive immune system. Adaptive immunity is the ‘precision’ branch of the immune system that targets specific, individual antigens. By definition, antigens are substances the body recognizes as foreign and potentially harmful, including various parts of germs.

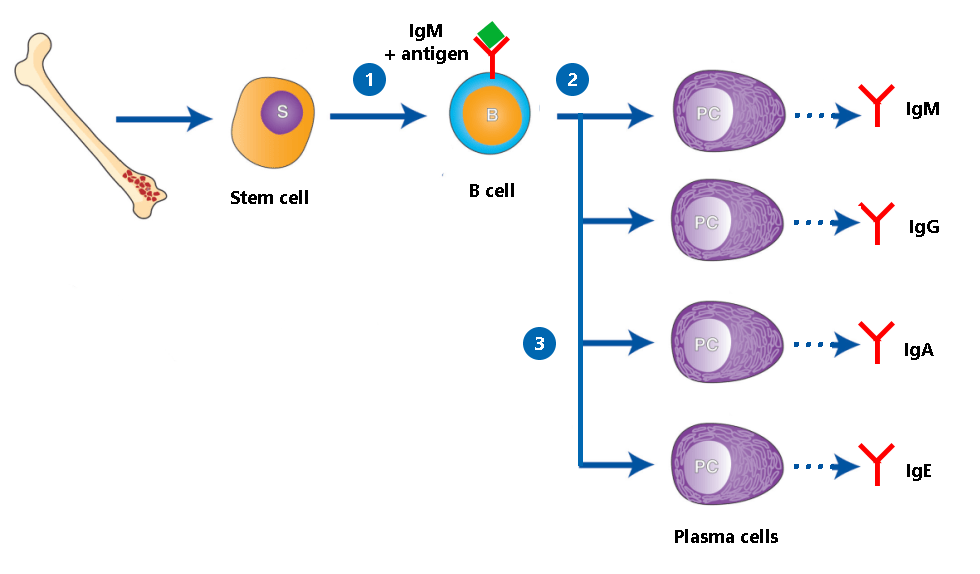

Antibodies are produced by a type of white blood cell called B cells. Each B cell makes a different antibody that recognizes and binds to one specific antigen like a lock and key. When a B cell comes in contact with the antigen its antibody recognizes, the B cell matures into a plasma cell, whose job is to pump out as much of that antibody as possible.

The antibody then contributes to the overall immune response by directly binding to the antigen. Antibody-antigen binding can physically block a germ from infecting cells or tag it for other immune system weapons, like the complement system (which punches holes in bacteria) or phagocytes (cells that swallow and digest their targets).

Without the right antibody, though, the immune system has trouble ‘seeing’ and targeting the foreign antigen and the germ it’s from. That’s why those with antibody deficiencies have trouble fighting off infections.

The immune system produces five different classes, sometimes called isotypes, of antibodies. Antibody deficiencies are a spectrum of disorders. Some affect all classes of antibodies, while others only affect a particular class or subclass of antibody.

- IgM: The first class of Ig made by B cells is IgM. IgM molecules are anchored on the surface of the B cells that produce them. After the IgM on a B cell detects an antigen, the B cell makes copies of itself. Those copied cells then ‘class switch’ to make the other Ig classes listed below as they develop into plasma cells. However, regardless of Ig class, the antibodies produced remain specific to the antigen that was originally detected.

- IgG: IgG is the ‘main’ or most abundant class of Ig that circulates in your bloodstream. It circulates as a single molecule and has four subclasses, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 that bind different types of antigens.

- IgA: IgA has two subclasses, IgA1 and IgA2. IgA1 circulates as single molecules in your blood, but IgA2 is two IgA molecules connected together and is found in mucous membrane fluids like tears and phlegm, and in breast milk. IgA2 provides protection against infection at mucous membranes like those in the respiratory tract and the gastrointestinal tract.

- IgD: Made by B cells, IgD’s function is currently murky.

- IgE: IgE is a small fraction of overall Ig that targets parasites and is also involved in allergies. It circulates in your bloodstream attached to white blood cells.

What to know about antibody deficiencies

The ‘classic’ symptom of an antibody deficiency is frequent, severe, and/or recurring infections, including pneumonia, sinus infections, gastroenteritis, skin infections, and sepsis. Generally, the more classes of antibodies impacted, the more severe a person’s antibody deficiency symptoms. For example, someone with a deficiency in IgG and IgA is likely to have more frequent and severe infections than someone with only a deficiency in IgA, who may have no symptoms. The same goes for antibody levels—someone with no IgG generally has more severe symptoms than someone with low IgG. Antibody deficiencies can also cause autoimmune or autoinflammatory symptoms, like inflammatory bowel disease or lupus.

It’s also important to know that individuals sometimes have more than one type of antibody deficiency. For example, there are people who have both selective IgA deficiency and IgG subclass deficiency. In addition, a person’s type of antibody deficiency can shift as they age, such as a child with selective IgA deficiency who develops common variable immune deficiency (CVID) as an adult.

Researchers have linked some antibody deficiencies, like X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), to specific genetic variants. Others, like CVID and selective IgA deficiency, remain a mystery genetically. At the same time, there is clear evidence that antibody deficiencies without known genetic causes run in families—for example, close relatives of those with selective IgA deficiency are more likely to have CVID or selective IgA deficiency than the general population.

How antibody deficiencies differ from each other

There are multiple distinct diagnoses under the antibody deficiency umbrella. While they may have similar symptoms, knowing which one you have can help determine the best treatment for you, what to expect, and how likely family members are to be affected.

Agammaglobulinemia

Agammaglobulinemia is the most severe form of antibody deficiency. People with agammaglobulinemia have no or very low antibody levels across all types that are typically measured (IgG, IgM, and IgA). In addition, a low percentage of their white blood cells are B cells, or they don’t have B cells at all, a condition known as B cell lymphocytopenia.

The first PI to be discovered was XLA, a type of agammaglobulinemia, but there are also autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant forms of the disorder. Variants in 14 different genes, all of which are involved in the development of B cells from bone marrow stem cells, can cause agammaglobulinemia. These variants disrupt the ability of a person to make B cells, and with no or low B cell levels, few, if any, antibodies get made.

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID)

CVID is an umbrella diagnosis that most likely covers several disorders with overlapping symptoms. Whereas those with agammaglobulinemia have no or extremely low antibody levels, people with CVID have hypogammaglobulinemia, which means low, but not absent, levels of antibodies. Researchers suspect that people with CVID cannot develop plasma cells from their B cells.

Clinicians don’t agree on a single definition or set of diagnostic criteria for CVID. The diagnosis generally applies to people older than 4 years of age who are symptomatic (e.g., have infections or autoimmune or autoinflammatory symptoms) and have:

- Low serum IgG levels.

- Plus, low serum levels of IgA and/or IgM.

- Low functional antibodies (typically demonstrated by poor vaccine response).

- No other known cause for the antibody deficiency, such as leukemia.

Those diagnosed with CVID seem to fall into two categories, with about 30% experiencing only infections and 70% experiencing non-infectious complications like autoimmune disease as well.

The genetic variant(s) responsible for CVID have not been identified. However, some newly discovered antibody deficiencies caused by variants in single genes have ‘peeled off’ patients initially diagnosed with CVID. For example, activated PI3K delta syndrome (APDS) was first described in 2013, and individuals with APDS are still misdiagnosed with CVID. For this reason, many immunologists encourage people with CVID to get genetic testing for single-gene disorders that mimic CVID.

Other types of hypogammaglobulinemia

As mentioned with APDS, over time, researchers have discovered genetic variants that lead to CVID-like disorders with low IgG, plus low levels of either IgA and/or IgM. Variants in 23 genes cause hypogammaglobulinemia similar to CVID.

Hyper IgM syndromes

The most common and well-studied hyper IgM syndromes, such as CD40 ligand deficiency (also known as X-linked hyper IgM), are combined immunodeficiencies affecting antibody production and T cell immune responses. They can be severe and may require treatment with a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). However, there are certain hyper IgM syndromes, like activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency, that are less severe and mainly impact a person’s ability to produce antibodies.

All hyper IgM syndromes result from variants in genes involved in the ‘class switching’ process—that is, the process where T helper cells interact with B cells to ‘switch’ the B cells from making IgM to making either IgA, IgE, or IgG antibodies. In all cases, this switching doesn’t happen as it should, so individuals have normal or high levels of IgM but low levels of other antibody classes.

Some genes involved in class switching, like CD40 or CD40L, are also necessary for T cell function. That’s why variants in these genes lead to more severe hyper IgM syndromes. Others are involved further along in the class-switching process, so variants in these genes lead to milder hyper IgM syndromes.

Single type or subtype antibody deficiencies

Antibody deficiencies that affect a single type or subtype of antibodies tend to be the least severe and sometimes cause no symptoms at all. The most common of these deficiencies are selective IgA deficiency, IgG subclass deficiency, and specific antibody deficiency.

Some individuals ‘grow out’ of their single type or subtype deficiencies, while others develop a broader antibody deficiency like CVID. This observation suggests that, in some cases, the single type or subtype deficiency may be the first sign of a broader antibody deficiency rather than a stand-alone condition.

- Selective IgA deficiency: As its name suggests, selective IgA deficiency is when someone has little to no IgA but normal levels of IgG and IgM. These individuals essentially lack antibody protection at mucosal barriers where germs ‘get in’ to the body, but they still have protection from IgG in their bloodstreams.

- This is the most common type of antibody deficiency in those with European ancestry.

- Most people with selective IgA deficiency do not have symptoms or have symptoms so mild that they don’t seek a diagnosis. Some do have recurrent sinus, respiratory, or gastrointestinal infections.

- Those with symptoms are more likely to go on to develop CVID.

- IgA deficiency correlates with several autoimmune conditions and allergies, especially celiac disease.

- IgG subclass deficiency: Some people have adequate overall levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM but low levels of a particular subtype of IgG.

- As with selective IgA deficiency, most people with IgG subclass deficiency alone don’t have significant symptoms. However, some people experience reoccurring infections such as pneumonia, ear infections, or sinus infections.

- This diagnosis covers individuals who have low levels of IgG2, 3, or 4. IgG1 makes up such a large fraction of over IgG that low IgG1 typically results in hypogammaglobulinemia and a diagnosis of CVID or a related disorder.

- IgG subclass deficiency also correlates with several autoimmune conditions and allergies.

- Specific antibody deficiency: People with specific antibody deficiency have adequate levels of antibodies, but they do not produce antibodies specific to the sugar (polysaccharide) antigens that are crucial for the immune system to recognize certain types of bacteria.

- This deficiency can be mild, moderate, or severe depending on how many antigens do not cause the person to produce effective antibodies.

- People with this deficiency get upper and lower respiratory infections from certain bacteria like Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae.

The antibody deficiencies mentioned above are the most common types, but there are other, less common antibody deficiencies as well. And, as with any biological condition, some people fall outside of the diagnostic criteria for all defined antibody deficiencies, even though they clearly have a similar condition. This group includes people with low total IgG alone or with multiple low Ig classes but normal vaccine response—conditions that don't quite meet the criteria for CVID. Healthcare providers may refer to these individuals as having 'unspecified hypogammaglobulinemia' or 'unspecified antibody deficiency.' Future research could define new, specific diagnoses for these individuals.

Screen documentary

Host a private screening of Compromised: Life Without Immunity to experience the resilience, hope, and determination of the PI community. And know that your hosted event can be two people or 100+!

Watch the filmRelated resources

IDF Patient & Family Handbook for Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases, Sixth Edition (Korean)

Manual para pacientes y familias sobre inmunodeficiencias primarias, sexta edición

Decoding PI: Unraveling the GI connection

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309