-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Grants

-

IDF surveys

-

Participating in clinical trials

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Clinician education

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Grants

Cindy Cutshall-Kisik visits youth of all ages – from preschool to college – to share the importance of addressing mental health needs. She tells them not to be ashamed if they feel sad or anxious, that’s it’s normal, and there are people in the community who want to help. Don’t let your problems fester, and don’t be embarrassed to ask for help, she says.

“Your mental health is just as important as anything else and you won’t be able to help others unless you help yourself,” said Kisik.

While Kisik received a lot of attention as a child and young adult for being the second person in the world to receive gene therapy to treat adenosine deaminase severe combined immunodeficiency (ADA-SCID) and she is happy to share her rare disease story, these days she is more focused on being an advocate for mental health.

Kisik works part-time for the local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) in her hometown of Stark County, Ohio as an outreach coordinator. As part of her job, she created a kid-friendly activity book that introduces children to mental health challenges and explains how it’s not their fault, and that they should talk about their emotions and feelings.

“It’s probably one of the things that I am most proud of,” said Kisik.

At the root of her deep interest in mental health is Kisik’s experience juggling her diagnosis and subsequent treatment (which garnered worldwide attention) while simply trying to live her life as a child and teen.

Born on July 6, 1981, to Susan Cutshall, a nurse, and William Cutshall, a respiratory therapist, Kisik developed pneumonia six times during infancy and early childhood and landed in the hospital for a month due to chicken pox. Neither doctors nor her parents could figure out why she constantly developed infections, particularly because her lymph nodes were never swollen.

The turning point for her diagnosis occurred when Kisik was about 4 years old and came home from school limping. Doctors discovered that an infection in her sinuses had traveled through her blood to one of her hip joints, causing a severe hip infection. Doctors performed surgery to drain the infection and prescribed intravenous antibiotics at home for four weeks.

A subsequent referral to an immunologist at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital revealed the source of Kisik’s health problems – ADA-SCID. A person with ADA-SCID lacks the ADA enzyme, which is necessary to prevent the build-up of a toxic substance called deoxyadenosine. This harmful substance kills immune system cells. ADA-SCID is the second most common type of SCID next to X-linked SCID.

Kisik entered clinical trials for enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) – which eventually gained FDA approval – and her health improved. Still, ERT, which requires weekly intramuscular injections and can have side effects, is not a long-term treatment for ADA-SCID.

In 1990, at the age of 9, Kisik and her family agreed to participate in a clinical trial gene therapy treatment for ADA-SCID at the National Institute of Health (NIH), in hopes that it would be a more permanent solution to alleviate the ADA-SCID. Kisik recalls being afraid of joining the trials but also understanding that she could be contributing to the greater good.

“I remember signing the papers and thinking if this can help other kids, then I definitely want to do it, and if it doesn’t work, we’ll try something else,” she said.

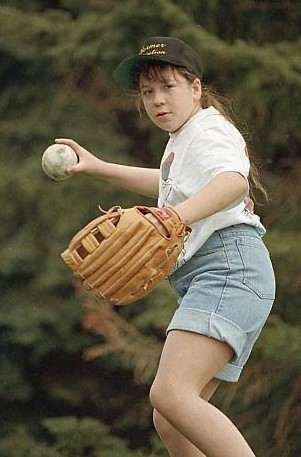

For a year and a half, Kisik visited the NIH monthly to undergo apheresis - a process in which her T cells were collected and the rest of her blood was returned to her body - and infusions of her own gene-corrected cells. Her immune system improved and within two years she became livelier and more active, just like any other teen. She played with friends, started summer softball, rode bikes, and went to slumber parties. Once in high school, Kisik joined marching band, theater, and chorus.

“I could do the things that typical kids could do and didn’t have to worry about getting sick,” she said. “That’s when I knew something was going on. I’d never felt so energetic.”

Though Kisik felt good physically, she struggled emotionally because of the psychological impact of lengthy sicknesses and hospital stays. She found help through a therapist and realized that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is not just a diagnosis for those in the military. PTSD can also occur in those who have undergone medical trauma.

“It was difficult for me to understand that you could have PTSD and not be a soldier. Even now, it’s difficult for people to understand but for those who have trauma – you know,” said Kisik.

Kisik said that her sister, Laura McCoul, also provided her with strength.

“Oftentimes, siblings are left to feel like they aren’t as important or feel left behind because so much focus is on the patient,” said Kisik. “Laura has been such a support to me and is my best friend. It wasn’t always easy being a sister to a SCID kid, but she was always there for me.”

Family members of children with SCID should seek support in coping with their stress, added Kisik’s mother, Susan Cutshall.

"Continuous worry about the next infection is always on everyone's mind. Family members need to have help with dealing with the emotions of having a sick child,” said Cutshall. “The constant concern of making sure they are doing everything possible for their child, leaves little room for looking out for their own health, both mental and physical.”

After graduation, Kisik attended Kent State University but decided to take time off and continue to address her PTSD, depression, anxiety, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Kisik also felt guilt for surviving her diagnosis when she saw other children in the hospital succumb to their diseases.

“It was a dark time,” said Kisik.

Kisik enrolled in a mental health recovery program and then returned to college, earning an occupational therapy assistant certification. She now works part-time in the school setting, providing services to children ages kindergarten through eighth grade.

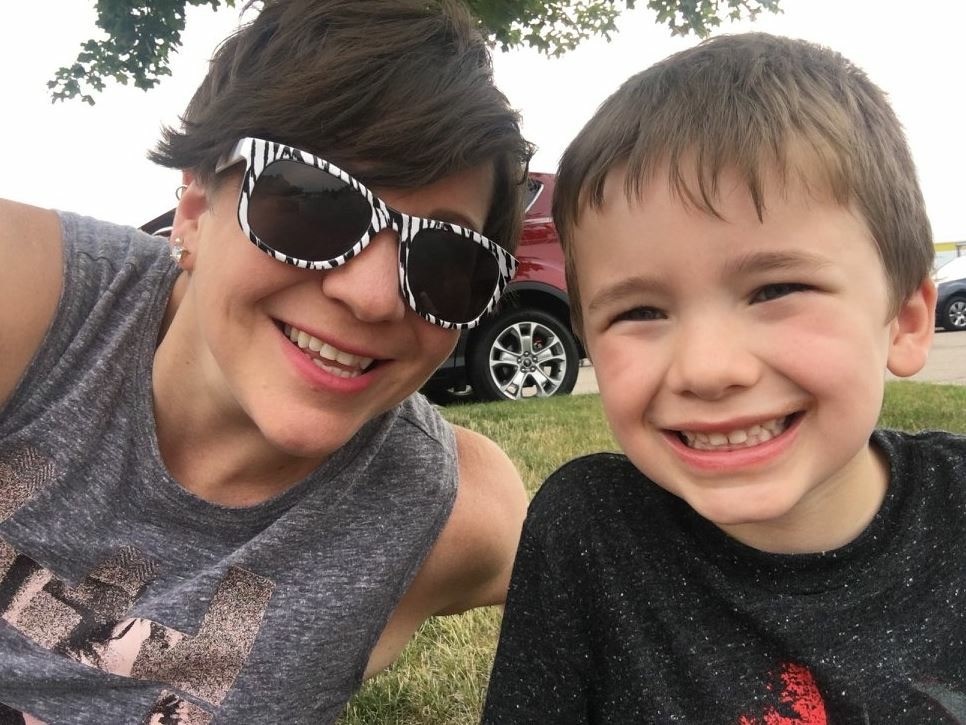

When she’s not working, Kisik enjoys hiking and fishing with her husband Christopher, and their dog Kevin, and lifting weights to relax. She’s also particularly close with her 11-year-old nephew Riley Cutshall.

“We love just hanging out and goofing off together,” said Kisik.

Kisik connected with IDF as a 13-year-old in 1996 when she shared her story about ADA-SCID and gene therapy at an IDF National Conference. In addition to attending IDF conferences, she worked as part of the grassroots campaign to have SCID placed on the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), a list of disorders the federal government recommends states screen as part of their newborn screening programs.

Most recently, Kisik helped IDF develop teen and young adult programming, and you can browse more helpful teen and young adult resources on our website. Additionally, she enjoys being a mentor to youth with PI and wants them to know that they can achieve anything they want despite their diagnosis.

“I remember what it was like because I didn’t have anyone there for me. It’s so important to have camaraderie and be with people who get it,” she said. “Plus, I think helping out actually helps me, too.”

Kisik said each person’s mental health is their own journey and she encourages every person, not just those with PI, to talk with others about their problems.

“Whatever you go through with mental health, your journey will be different from anyone else’s, but we all have the same feelings and that’s what makes us more of a community,” said Kisik. “We don’t have to do this alone anymore.”

Related resources

Thirty-year-old with APS type 1 advocates for her community

Susan finds "priceless" support system in the Immune Deficiency Foundation

Mother details harrowing journey to son's diagnosis and relief of finding the PI community

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309