-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Grants

-

IDF surveys

-

Participating in clinical trials

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Clinician education

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Grants

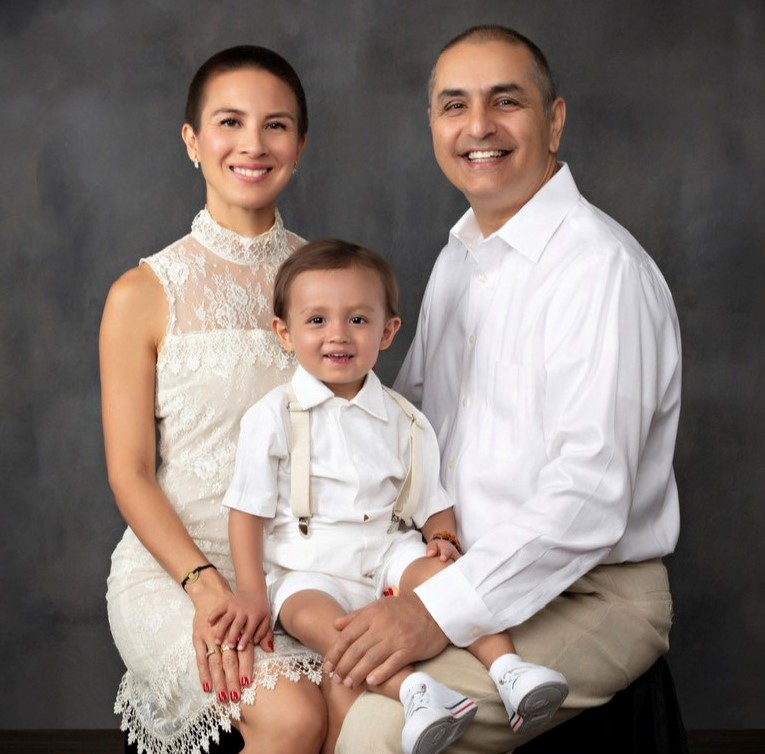

In August 2021, mom Crystal Cruz, dad Chahriar Assad, and their son Cyrus Bakhtiari took a family vacation and contracted COVID-19 on their trip. Mother and father developed symptoms but easily shook the virus. Cyrus, a toddler, didn’t fare as well.

“He started to become very lethargic, just really out of it,” said his mother. “He wanted to be carried, and he was tired, and he slept a lot, and he was regressing. I kept asking the pediatrician, is this OK for children with COVID to be so sick?”

One day, about a month after getting the virus, Cyrus pointed to his side, near his appendix, guarding it. Alarmed by his gestures, Cruz took him to urgent care. At first, doctors diagnosed him with constipation, but bloodwork revealed he had a raging infection with highly elevated inflammation markers.

“This was definitely alarming and very scary,” said Cruz.

Doctors admitted Cyrus into Children’s Hospital Los Angeles after the family waited eight hours in the emergency room, and extensive testing began – more bloodwork, scans, x-rays, and an echocardiogram. All the while, his mother thought Cyrus suffered from multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a complication of COVID. Then doctors offered up a different possibility – liver cancer.

“I thought, oh my gosh, my child is going to die of liver cancer,” said Cruz.

Eventually, doctors discovered Cyrus had a liver abscess, calcification in his lymph nodes, and lesions on his lungs. They intubated Cyrus to perform a gastric fluid analysis and placed a line into his liver to drain the infection. The toddler also received an intravenous line in his arm for medication and bloodwork. The veins in Cyrus’s arms constantly collapsed, causing nurses to stick the toddler with needles repeatedly, and his mother begged for a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC line).

“It was all too much,” said Cruz.

After two weeks, doctors finally reached the correct diagnosis—chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a rare primary immunodeficiency (PI). Cruz and Assad, along with Cyrus, had undergone genetic testing early on in Cruz’s pregnancy but not the type that would show Cyrus had CGD—or that Cruz was a CGD carrier.

“We were floored,” said Cruz, who was 38 when pregnant with Cyrus, her first child. “I had no idea what CGD was. No one in my life knew.”

As an infant, Cyrus had developed multiple small skin infections that wouldn’t heal, but there were no major red flags that indicated a serious health problem.

“He was kind of getting sick, but not very sick,” recalls Cruz.

The hospitalization that led to Cyrus’s CGD diagnosis at 18 months old lasted for six weeks. During that time, as her son battled infection, Cruz felt isolated and overwhelmed by the lack of resources about CGD.

“Living in the hospital presents its own challenges, and what I realized is there is no system in place to be connected in an effective manner. I was trying to advocate for myself and be the glue and make sure they all knew what was going on,” she said.

“I continue to this day earning a medical degree on the job.”

Cruz researched CGD online and sought out other families living with the same diagnosis. Communication with the National Institutes of Health led her to the Chronic Granulomatous Disease Association of America (CGDAA), a nonprofit led by Felicia Morton, the mother of a child diagnosed with CGD.

“My life changed; it did a 180. She connected me to everyone and everything,” said Cruz. “She also walked the walk. I could talk to her and connect with other moms, so we had people reaching out to us through different channels, and we got a really good grasp on what this is like and how it affects families.”

Cruz and Assad expressed interest in bone marrow transplant (BMT), a long-term treatment for CGD, but they couldn’t proceed because Cyrus’s liver had to heal, and providers needed time to find a matched stem cell donor. Instead, they treated Cyrus with preventive antibiotics and antifungals, and liver medication and kept him away from crowded places.

“It felt like we had a long time to decide because the liver was healing, and throughout this time, our life resumed. I’m taking Cyrus out, but no one is touching him. It’s our way of integrating into our life now that we have a child with PI,” said Cruz. “It prevents us from socializing with kids because of all the germs they tend to carry, and we want to minimize the sicknesses and hospital stays.”

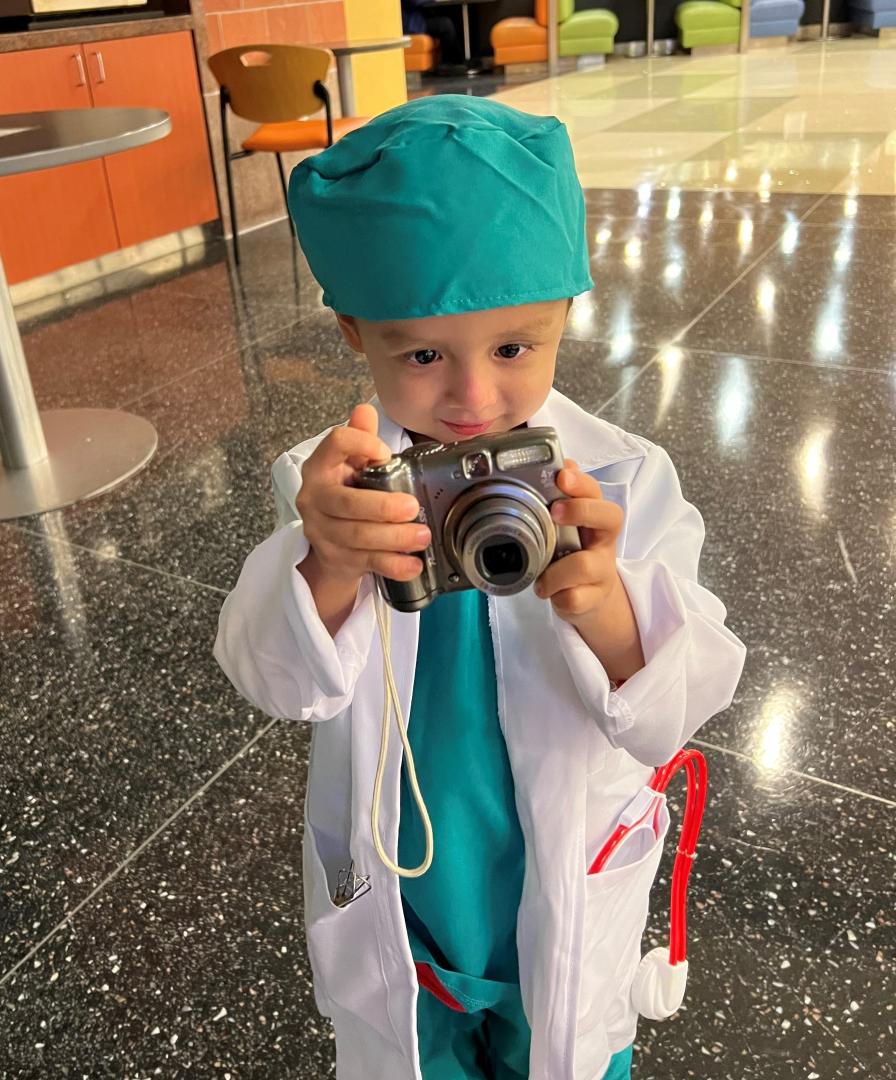

Though Cyrus avoided socializing, his parents made sure they supported their son’s curiosity in activities that brought him happiness. Cyrus enjoys taking photos and videos, hitting baseballs, dancing, listening to music, especially classical music, and playing the violin and drums. His family took him to see Native American drumming at a pow-wow and a performance of Japanese Taiko drumming.

“We’re doing all these things, and he’s living a normal happy life,” said his mother.

As the months passed in 2022, scans showed promise that Cyrus’s liver was healing, but one day in September, he pointed to his chest and cried – then vomited. Cruz whisked him to the hospital.

“That was frightening. That was not on our radar to get another infection again. My husband and I panicked on that Monday when he was going to be admitted. That was the day they were supposed to meet with the BMT team,” she said.

Cyrus suffered from dilated bile ducts in his gallbladder, and he remained in the hospital for a month and a half. Meanwhile, doctors told the family they had a matched stem cell donor for Cyrus, which would allow them to move forward with BMT treatment.

The family decided not to treat Cyrus with BMT.

“We felt like we had to do it very fast, and we realized we were jumping into a life-altering decision out of fear,” said Cruz.

Cyrus, almost three years old, is back home and on medication, which is thousands of dollars a month out-of-pocket, said Cruz, and he undergoes weekly blood draws to monitor his health. The family is currently in a holding pattern, trying to decide the next steps they should take to help their son.

Cruz feels that sharing her family’s story brings awareness to CGD and the challenges families face in deciding how to proceed with treatments.

“It’s so hard to understand what is best for my child,” said Cruz. “As a parent and as a mother, what’s helpful is talking about things, so I feel very comfortable sharing our story.”

Follow the family’s journey with CGD on Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok, at @healingwithcyrus.

Related resources

Thirty-year-old with APS type 1 advocates for her community

Susan finds "priceless" support system in the Immune Deficiency Foundation

Mother details harrowing journey to son's diagnosis and relief of finding the PI community

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309