Genetic testing

Genetic testing looks for variants in genes that are known to cause primary immunodeficiency (PI) and may fast-track your diagnosis.

Genetic testing looks for variants in genes that are known to cause primary immunodeficiency (PI) and may fast-track your diagnosis.

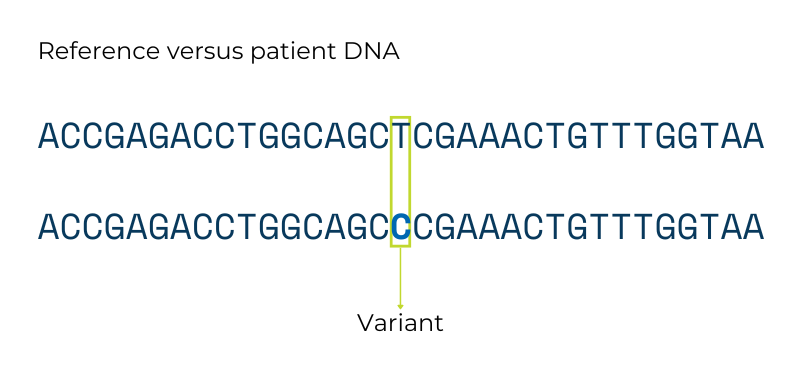

Primary immunodeficiencies (PIs), also known as inborn errors of immunity (IEIs), are disorders caused by changes, or variants, in a person’s DNA. Four nucleotides make up DNA: adenine (A), thymidine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). The order of these nucleotides, or the DNA "sequence," encodes instructions for making proteins, cells, and organs, similar to how specific sequences of letters form words, sentences, and paragraphs.

Variants in the DNA sequence lead to genetic differences between people. Genetic testing looks for these variants. Some variants do not significantly change the overall genetic instructions, and those variants do not cause disease. Other variants do significantly change the instructions, and those types of variants can cause genetic conditions like PI.

Healthcare providers use genetic testing to confirm a diagnosis based on clinical symptoms or laboratory test results, or to reach a more precise diagnosis if symptoms don’t point to a particular disorder. Genetic testing can also determine if someone who does not yet have symptoms is at high risk for developing PI.

Results from genetic testing can not only provide a genetic diagnosis by pinpointing the gene variant responsible for PI but can also inform treatment and clinical management, family planning decisions, and whether relatives are at risk of PI. For example, several genetic variants with different patterns of inheritance cause chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). Knowing which variant an individual with CGD has is key for family planning and understanding who else in the family is at risk.

Genetic testing is a powerful tool. However, it’s important to understand that all of us have differences in our DNA compared to other people, and not all genetic variants are harmful or cause medical conditions. In addition, the genetic basis for some of the most common types of PI remains unknown, so not everyone who gets genetic testing will receive a genetic diagnosis. For some people, genetic testing will only rule out variants they do not have.

Information from genetic testing is more sensitive than other types of medical information. In 2008, Congress passed the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act (GINA). GINA bans employers and health insurance companies from using genetic information in employment or coverage decisions. GINA also clarified that genetic information is a type of medical information subject to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy rules.

However, GINA has limitations. For example, the military is exempt from its employer regulations and genetic information can legally be used to determine someone’s eligibility for life or long-term care insurance. In addition, law enforcement can subpoena genetic information from medical records, which could implicate an individual or their relatives in a crime.

In addition to being used in ways you may not agree with, your genetic testing results can reveal information you may not anticipate. This information can range from secondary findings that identify a genetic condition aside from PI to learning that your presumed parents are not your biological parents. Genetic counselors can help individuals understand and think through these scenarios before undergoing genetic testing.

Unlike other types of medical tests, your genetic sequence does not change over time. That means that your raw genetic data can be reanalyzed periodically as labs update their lists of PI-related or immune system-related variants and reclassify VUS. Be sure to retain a copy of your test results and consider contacting the provider who ordered the testing or the testing facility to request updates every couple of years if your condition remains undiagnosed.

Panel testing, WES, and WGS can identify gene variants not only in individuals with PI but in their unaffected family members. In cases of a family history of autosomal recessive or X-linked recessive PI, family members, such as the parents or siblings of the person with PI, can undergo carrier testing. Carrier testing determines if someone ‘carries’ one copy of a gene variant linked to PI. In most cases, carriers do not themselves have PI symptoms, although there are exceptions, such as women who carry the variant that causes X-linked chronic granulomatous disease (CGD).

Prospective parents should seek information from healthcare professionals such as pediatricians, genetic counselors, immunologists, and obstetricians on current medical advances relating to the PI of concern. Genetic counseling is highly recommended in families with a known history of PI, as it allows the option for early detection, diagnosis, and treatment.

A few questions to ask your provider:

There are currently two sponsored, no-charge genetic testing programs available for people who are suspected of having either APDS (activated PI3K delta syndrome) or chronic neutropenia/WHIM syndrome. Both programs include pre- and/or post-testing genetic counseling services that provide support to help your family better understand the testing process, what to anticipate in terms of results, and what information is needed by your physician.

Talk to your provider to determine if you meet the criteria to qualify for either genetic testing program.

This program is available to patients in the U.S. and Canada who meet any two or more of the following bulleted criteria below:

Clinical features:

Labs:

History:

This program is available to patients in the U.S. and Canada who meet all three of the following criteria:

This page contains general medical and/or legal information that cannot be applied safely to any individual case. Medical and/or legal knowledge and practice can change rapidly. Therefore, this page should not be used as a substitute for professional medical and/or legal advice. Additionally, links to other resources and websites are shared for informational purposes only and should not be considered an endorsement by the Immune Deficiency Foundation.

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.